The greatest threats to coral reefs from well-intentioned visitors are often invisible, stemming from misunderstood chemical ingredients and subtle physical interactions.

- “Reef-safe” labels can be misleading; the key is to look for non-nano mineral ingredients and avoid a specific list of toxic chemicals.

- Protecting coral is less about not touching and more about actively mastering buoyancy to control your physical footprint in the water.

Recommendation: Shift your mindset from a passive tourist to an active guardian by learning to identify these hidden risks before you even enter the water.

The desire to witness the vibrant, bustling cities of a coral reef is a powerful one, especially in an era where their future is uncertain. You’ve seen the documentaries, you know the basic rules: don’t touch, don’t stand, don’t take. As an eco-conscious traveler, you’re already a step ahead. Yet, a nagging fear remains—what if, despite your best intentions, you are inadvertently contributing to the problem you care so deeply about? This anxiety is valid, because the most common advice often only scratches the surface of responsible interaction.

Most guides will tell you to wear “reef-safe” sunscreen and be a mindful swimmer. While true, this guidance fails to address the deeper complexities. The issue isn’t just about avoiding a few banned chemicals or keeping your hands to yourself. True reef stewardship involves a more profound understanding of your impact, from the unseen chemistry leaching off your skin to the subtle water pressure created by your fins. It requires you to think less like a tourist and more like a conservationist.

But what if the key wasn’t just following rules, but mastering a set of principles? What if you could learn to read a sunscreen label like a chemist, control your body in the water with the precision of a marine biologist, and understand the reef’s architecture to appreciate its fragility? This guide is built on that premise. We will move beyond the platitudes to explore the invisible threats and provide you with the knowledge to transform your fear into confident, positive action. We will dissect what “reef-safe” truly means, teach you to control your physical footprint, and reveal the hidden dangers and ecological secrets of the reef, ensuring your visit is one of observation, not interference.

This article provides a comprehensive framework for interacting with coral ecosystems responsibly. Explore the sections below to understand the specific actions you can take to become a true guardian of the reefs you visit.

Summary: A Deeper Dive into Responsible Reef Visitation

- Why Your “Reef-Safe” Sunscreen Might Still Be Toxic?

- How to Control Your Floatation to Avoid Kicking the Coral?

- Artificial Reef or Natural Garden: Which Has More Fish Density?

- The Infection Risk of a Coral Scratch That Travelers Ignore

- When to Visit the Great Barrier Reef to Avoid Stinger Season?

- Why Your Sunscreen Might Be Killing the Ecosystem You Came to See?

- Why Are There More Fish Around Branching Coral Than Massive Coral?

- How to Visit Fragile Ecosystems Without Leaving a Negative Footprint?

Why Your “Reef-Safe” Sunscreen Might Still Be Toxic?

The term “reef-safe” on a sunscreen bottle can feel like a green light for responsible use, but unfortunately, it’s often a marketing ploy with no regulated definition. Many products avoid the two most infamous ingredients, oxybenzone and octinoxate, yet contain other chemicals that are just as, if not more, harmful. With an estimated 8,000 to 16,000 tons of sunscreen washing into coral reef areas annually, understanding what’s truly safe is critical. The chemical footprint you leave behind is one of the most significant, yet invisible, impacts of your visit.

The only truly reef-safe sunscreens are those that use non-nano mineral filters: zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. These ingredients form a physical barrier on your skin rather than a chemical one. However, the “non-nano” part is crucial. Nano-sized particles (smaller than 100 nanometers) are so small they can be ingested by corals, causing internal damage. A truly safe product will explicitly state its ingredients are “non-nano” or have a particle size above this threshold. As a conservationist-minded traveler, your first line of defense should always be physical barriers like a UPF (Ultraviolet Protection Factor) rash guard, hat, and leggings, which eliminate the need for sunscreen on large parts of your body altogether.

Djordje Vuckovic, a PhD student at Stanford University involved in a key study on sunscreen toxicity, makes the point unequivocally. His research highlights how certain chemicals, once absorbed by coral, are metabolized into potent toxins when exposed to sunlight.

Oxybenzone should not be in coral-safe or reef-friendly sunscreens

– Djordje Vuckovic, Stanford University Study on Sunscreen Toxicity

To avoid being misled, you must become a label detective. Ignore the front of the bottle and go straight to the “Active Ingredients” list on the back. If you see anything other than non-nano zinc oxide or titanium dioxide—especially chemicals like octocrylene, avobenzone, or homosalate—the product is not safe for marine ecosystems, no matter what the marketing claims.

How to Control Your Floatation to Avoid Kicking the Coral?

Beyond your chemical footprint, your physical footprint is the most direct threat you pose to a reef. Unintentional contact, often from fins, knees, or hands, can break decades-old coral structures in a split second or scrape away the thin layer of living tissue, leaving the coral skeleton vulnerable to algae and disease. The key to avoiding this is not just “being careful,” but mastering the skill of buoyancy control. It is an active, not passive, state of being in the water, allowing you to float effortlessly and neutrally, like another piece of marine life.

The first step is achieving a horizontal float, keeping your body parallel to the surface. This posture naturally lifts your fins up and away from the coral below. Many swimmers, especially less confident ones, tend to adopt a more vertical, “sea-horse” position, which dangles their fins directly over the reef. A simple trick is to use a snorkeling vest or a wetsuit. Even for strong swimmers, these aids provide effortless buoyancy, allowing you to focus on observation rather than on the physical effort of staying afloat. This stability minimizes the sudden, jerky movements that often lead to accidental kicks.

Your kicking technique is also paramount. Forget the big, splashy kicks of a surface swimmer. Instead, adopt the “lazy snorkeler’s kick”: small, controlled flutters originating from your hips, not your knees, with your ankles relaxed. This technique is more efficient, conserves energy, and dramatically reduces your underwater turbulence. The Green Fins initiative, a UN-backed program, has demonstrated that with proper training, diver and snorkeler impacts can be significantly reduced. For example, in Vietnam, their training led to a 20% reduction in environmental threats over two years by focusing on skills like buoyancy and environmental awareness. Before you even get near a reef, practice these techniques in a sandy area to understand how your body and equipment behave in the water.

Artificial Reef or Natural Garden: Which Has More Fish Density?

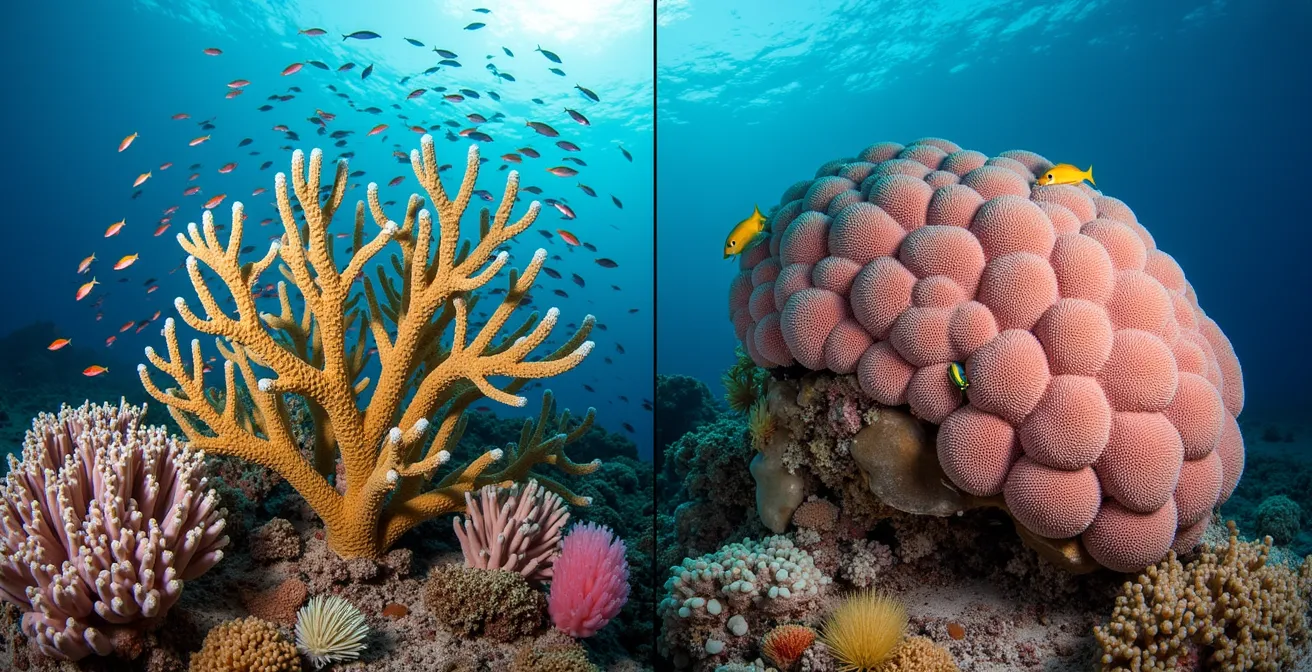

When we ask what type of reef supports more life, we’re really asking a question about architecture. It’s not about whether a reef is man-made or natural, but about its structural complexity. A coral reef is a three-dimensional city, and the more nooks, crannies, ledges, and hiding spots it offers, the more residents it can support. This is why different coral shapes create vastly different communities of fish and invertebrates. Understanding this ecological architecture is key to appreciating the life you are witnessing.

Imagine the difference between a high-rise apartment building and a sprawling suburban neighborhood. Branching corals, like staghorn and elkhorn, are the high-rises. Their intricate, tree-like structures create a dense maze of small spaces. This complex framework offers countless points of refuge for smaller fish, like damselfish and chromis, to hide from predators. It also provides a massive surface area for algae and invertebrates to grow, creating a rich food source. When you snorkel over a thicket of branching coral, you’re witnessing a bustling, high-density metropolis teeming with small, colorful life.

In contrast, massive corals, like brain or boulder corals, are the suburban homes. Their solid, mound-like forms provide shelter, but with far less complexity and fewer “apartments.” They are crucial to the reef’s foundation and protect coastlines from wave energy, but they don’t support the same sheer density of small fish. Instead, their larger, more open surfaces and overhangs tend to be used by larger fish, such as parrotfish or groupers, for resting or as cleaning stations. By learning to recognize these different structures, you begin to understand why you see certain fish in certain areas, transforming a simple swim into an ecological exploration.

The Infection Risk of a Coral Scratch That Travelers Ignore

While our primary focus is on protecting the coral from us, we must also be aware of the “invisible threat” the reef can pose to us. A seemingly minor scrape from a piece of coral is an injury that many travelers underestimate or treat improperly, leading to a risk of serious infection. Coral polyps are animals, and their skeletons are covered not only in their own living tissue and stinging cells (nematocysts) but also a biofilm of bacteria, algae, and microscopic marine organisms. When you are cut, these foreign materials are inoculated directly into your skin.

The body’s immune system often reacts aggressively to this foreign protein and bacteria, a condition colloquially known as “coral poisoning.” This isn’t a true venomous poisoning but rather a potent inflammatory response combined with a bacterial infection. The initial cut might look insignificant, but within days it can become intensely itchy, red, swollen, and may ooze fluid. Because the coral skeleton is brittle, tiny fragments can break off and remain embedded in the wound, preventing it from healing and serving as a constant source of irritation and infection. If left untreated, these infections can become systemic and require aggressive medical intervention.

Proper first aid is not optional; it’s mandatory and must be performed immediately. Saltwater is not a cleaning agent; it’s full of bacteria. You must exit the water and clean the wound thoroughly with fresh water and soap, gently scrubbing to remove any visible debris. Applying an antiseptic is the next step, followed by covering the wound to keep it clean and dry. Ignoring these steps, or simply waiting to “see what happens,” is a gamble with your health that can derail a trip and lead to lasting complications.

Your Action Plan: Emergency Protocol for a Coral Cut

- Immediate Evacuation and Rinse: Exit the water immediately. Rinse the wound thoroughly with clean, fresh water to remove salt, sand, and loose debris.

- Scrub and Clean: Gently but firmly scrub the area with soap and water. The goal is to physically remove all foreign material, including microscopic coral fragments that may be embedded in the skin.

- Apply Antiseptic: After cleaning, apply an antiseptic agent like povidone-iodine. Avoid hydrogen peroxide, as it can be too harsh and damage healthy tissue, slowing the healing process.

- Cover and Keep Dry: Cover the wound with a sterile, breathable bandage. Do your best to keep the wound dry until a solid scab has formed to prevent bacteria from entering.

- Monitor for Infection: Watch closely for warning signs: spreading redness from the wound site, the formation of pus, developing a fever, or seeing red streaks moving up a limb. If any of these occur, seek medical attention without delay.

When to Visit the Great Barrier Reef to Avoid Stinger Season?

Choosing when to visit a fragile ecosystem is a crucial part of minimizing your impact and maximizing your safety and enjoyment. For Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the decision is heavily influenced by a critical “invisible threat”: the stinger season. From roughly November to May, the warmer coastal waters become home to box jellyfish and the tiny, near-invisible Irukandji jellyfish. Stings from these species are excruciatingly painful and can be life-threatening, making a full-body “stinger suit” an absolute necessity for anyone entering the water.

While tour operators are well-equipped to manage this risk, many travelers prefer to visit outside this period for a more relaxed experience. The Australian winter, from June to August, is widely considered the peak season for this reason. The stinger risk is virtually zero, the weather is mild and dry with low humidity, and water visibility is generally good. This season also brings the awe-inspiring opportunity to witness the migration of dwarf minke whales and manta rays, adding a spectacular dimension to your visit.

However, planning your trip is about weighing trade-offs. The shoulder season of spring (September to November) offers what many consider the absolute best conditions. Water visibility can be exceptional, reaching up to 30 meters, and the stinger risk remains low until late in the season. Crucially, this is when the reef puts on its most magical show: the annual coral spawning event, a synchronized release of gametes that looks like an underwater snowstorm. It’s also the peak of turtle nesting season. The only downside is that you are approaching the warmer, more humid weather of the summer. The table below outlines these seasonal compromises to help you make an informed choice that aligns with your priorities.

This detailed seasonal guide helps travelers make informed decisions balancing safety, wildlife encounters, and weather conditions.

| Season | Months | Stinger Risk | Visibility | Wildlife Highlights | Weather |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | June-August | None | Good (15-20m) | Minke whales, manta rays | Cool, dry, 18-25°C |

| Spring | Sept-Nov | Low (late season) | Excellent (20-30m) | Coral spawning, turtle nesting | Warm, 22-29°C |

| Summer | Dec-Feb | High | Variable (10-20m) | Breeding seabirds, baby turtles | Hot, humid, 25-33°C |

| Autumn | March-May | Moderate-High | Good (15-25m) | Whale sharks, reef sharks | Warm, 23-30°C |

Why Your Sunscreen Might Be Killing the Ecosystem You Came to See?

The destructive power of chemical sunscreens lies in a sinister mechanism known as phototoxicity. It’s not just the presence of a chemical in the water that harms coral; it’s what that chemical becomes when exposed to the same sunlight it’s designed to protect us from. A groundbreaking study from Stanford University revealed this deadly transformation process using anemones, a close relative of corals. When the anemones absorbed oxybenzone, they didn’t just store it. Their metabolic processes converted it into phototoxic substances. When sunlight hit these new substances, they produced damaging free radicals that are lethal to the symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) living within the coral’s tissue.

This is the heart of coral bleaching. The zooxanthellae are the coral’s power source, providing up to 90% of its food through photosynthesis, and also giving it its vibrant color. When the algae are killed or expelled due to stress—from heat, pollution, or chemical toxins—the coral turns bone white and begins to starve. The concentration required to trigger this toxic effect is terrifyingly small. Some studies suggest toxicity can occur at levels as low as one drop of sunscreen in the equivalent of six and a half Olympic-sized swimming pools. This illustrates how even a small number of swimmers can contribute to a significant chemical load in a calm bay or lagoon with limited water circulation.

This microscopic process has macroscopic consequences. The chemical slick from thousands of visitors accumulates in the water and sediment, creating a chronic stressor for the entire ecosystem. It’s an invisible killer that undermines the reef’s resilience, making it more susceptible to other threats like warming ocean temperatures and disease. Therefore, choosing a truly reef-safe, non-nano mineral sunscreen is not just a “nice to have”; it is a fundamental act of conservation. It’s a conscious decision to prevent your personal protection from becoming a poison for the very ecosystem you traveled so far to admire.

Why Are There More Fish Around Branching Coral Than Massive Coral?

The answer lies in a single, critical ecological concept: habitat. Coral reefs are often called the “rainforests of the sea,” and for good reason. Though they cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, they are vital for the survival of an incredible amount of marine life. According to a report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, reefs provide habitat for at least 25% of all the world’s marine species. They are hotspots of biodiversity, and that diversity is directly tied to the physical structure the corals provide. For a small fish, structure is life. It is a place to hide, a place to feed, and a place to raise young.

Branching corals, with their complex, interwoven arms, are masters of creating what ecologists call “high-quality habitat.” They offer an almost infinite number of small-scale hiding places. A juvenile fish can dart between the branches to escape a predator, a behavior you can easily observe while snorkeling. This three-dimensional maze offers protection from all angles, making it a perfect nursery for countless species. The immense surface area of these branching structures also acts as a substrate for algae and invertebrates to colonize, creating a constant, accessible buffet for herbivorous and omnivorous fish.

Massive corals, on the other hand, offer a different kind of service. Their large, solid forms are the bedrock of the reef, creating the primary framework and acting as breakwaters that protect coastlines. They provide shelter, but on a much larger and less intricate scale—think caves and overhangs rather than a dense network of tiny rooms. These spaces are more suited to larger creatures or nocturnal species seeking a resting place. While a healthy reef needs both types of coral architecture—the solid foundations and the intricate superstructures—it is the complexity of the branching corals that allows for the sheer density and diversity of smaller fish that make a reef feel so vibrant and alive.

Key Takeaways

- “Reef-safe” is an unregulated marketing term; always check the ingredient list for non-nano zinc oxide or titanium dioxide.

- Effective reef protection is an active skill, centered on mastering buoyancy and minimizing physical contact with the environment.

- The structural complexity of coral (e.g., branching vs. massive) directly determines the density and diversity of fish life it can support.

How to Visit Fragile Ecosystems Without Leaving a Negative Footprint?

Transitioning from a passive tourist to an active reef guardian involves synthesizing all these principles into a holistic approach that begins long before you touch the water. It’s about making a series of informed choices that collectively minimize your chemical, physical, and economic footprint. Your power as a consumer is immense. By choosing to support operators who have earned certifications like Green Fins or Blue Star, you are voting with your wallet for businesses that have invested in sustainable practices, such as using mooring buoys instead of dropping anchors that can smash coral.

Your preparation at home is just as critical. Packing UPF clothing reduces your reliance on sunscreen, and ensuring the sunscreen you do bring is truly mineral-based and non-nano prevents you from introducing harmful chemicals. The journey of an informed traveler is also one of lifelong learning. Engaging in citizen science by using apps like iNaturalist or CoralWatch to document what you see contributes valuable data to researchers monitoring reef health worldwide. It transforms your visit from a consumptive experience to a contributory one.

Ultimately, visiting a fragile ecosystem responsibly is about embracing a philosophy of respect and humility. As The SEA People Organization notes, tourism has a dual role, offering both incredible benefits and potential harm. It can support local economies and fund conservation, but only when practiced with care and foresight. By understanding the invisible threats, mastering your presence in the water, and making conscious choices on land, you ensure that your visit falls on the positive side of that equation. You become part of the solution, helping to preserve the magic of these underwater worlds for generations to come.

Your journey to becoming a reef guardian starts now. Begin by evaluating your travel gear and booking with operators who prioritize the health of the ocean, ensuring your next underwater adventure is one that gives back more than it takes.