True marine identification isn’t about memorizing flashcards; it’s about reading the ecological story unfolding before you.

- Analyze body shape and swimming behavior before color to quickly identify family groups.

- Understand that habitat structure, such as the complexity of branching corals, dictates species diversity and density.

- Contribute to global research by systematically logging your sightings (and non-sightings) on citizen science platforms.

Recommendation: Master neutral buoyancy first. It is the non-negotiable foundation for all ethical and effective underwater observation.

For many divers, the underwater world is a mesmerizing blur of vibrant colors and fleeting shapes. The initial wonder of seeing a parrotfish or an angelfish is profound, yet it often evolves into a new kind of curiosity: “What exactly am I looking at?” The common approach involves flipping through waterproof fish ID cards or relying on a divemaster’s post-dive debrief. While helpful, these methods only scratch the surface, treating identification as a simple matching game based on color and pattern.

This approach is fundamentally limited. Underwater, light absorption at depth alters colors, and many species have different juvenile, adult, and regional colorations. The real key to understanding marine biodiversity lies not in a static visual checklist, but in adopting the mindset of a taxonomist. It involves observing the animal within its complete ecological context: its shape, its behavior, its preferred habitat, and its role in the ecosystem. This method transforms a passive viewing experience into an active scientific observation.

This guide will restructure your approach to marine identification. We will move beyond simple aesthetics to explore a systematic framework for observation. You will learn to recognize fish families by their movement, understand why certain habitats are bursting with life while others are sparse, and see how your observations can contribute to vital global research. The goal is to empower you to not just see marine life, but to understand it, and in doing so, become a more conscious and effective guardian of the ocean.

To help you navigate this new approach, this article is structured to build your skills progressively, from foundational identification techniques to advanced ecological awareness and conservation practices.

Summary: How to Identify Marine Life Like a Scientist (Without Disturbing a Thing)

- How to Use Patterns and Shapes to Identify Fish Families Instantly?

- Why Are There More Fish Around Branching Coral Than Massive Coral?

- Day Creatures vs. Night Hunters: Which Dive Reveals More Life?

- The Camouflage Mistake: How to Spot Stonefish Before You Touch Them?

- How to Log Your Sightings to Help Global Marine Research?

- Artificial Reef or Natural Garden: Which Has More Fish Density?

- Why Touching a Wild Animal Is Never Okay in a Real Sanctuary?

- How to Visit Fragile Ecosystems Without Leaving a Negative Footprint?

How to Use Patterns and Shapes to Identify Fish Families Instantly?

The first mistake in fish identification is focusing on color. A far more reliable method is to start with body shape and swimming motion, the two most consistent traits within fish families. Before your brain even registers color, it can process a silhouette. Is the fish elongated and serpentine like an eel, or laterally compressed and disc-shaped like a butterflyfish? Is it triangular and robust like a triggerfish? This initial classification narrows down the possibilities immensely.

Once you’ve categorized the shape, observe its behavioral signature, specifically its swimming pattern. A wrasse, for example, primarily uses its pectoral fins for a distinctive, flitting motion, as if it’s rowing through the water. In contrast, a parrotfish often “cruises” with powerful thrusts of its caudal (tail) fin. Jacks and tunas are built for speed, with stiff, streamlined bodies and forked tails, while a boxfish moves with an awkward, hovering motion propelled by tiny, whirring fins.

Finally, look at fin configuration and markings. Does it have a single long dorsal fin or two separate ones? Is the tail forked, rounded, or lunate? Markings like the false eye spots on many butterflyfish are designed to confuse predators and are a key identifier. By prioritizing this hierarchy of observation—shape, then motion, then details—you build a mental framework that works in any visibility and at any depth, turning a chaotic scene into an organized system.

Why Are There More Fish Around Branching Coral Than Massive Coral?

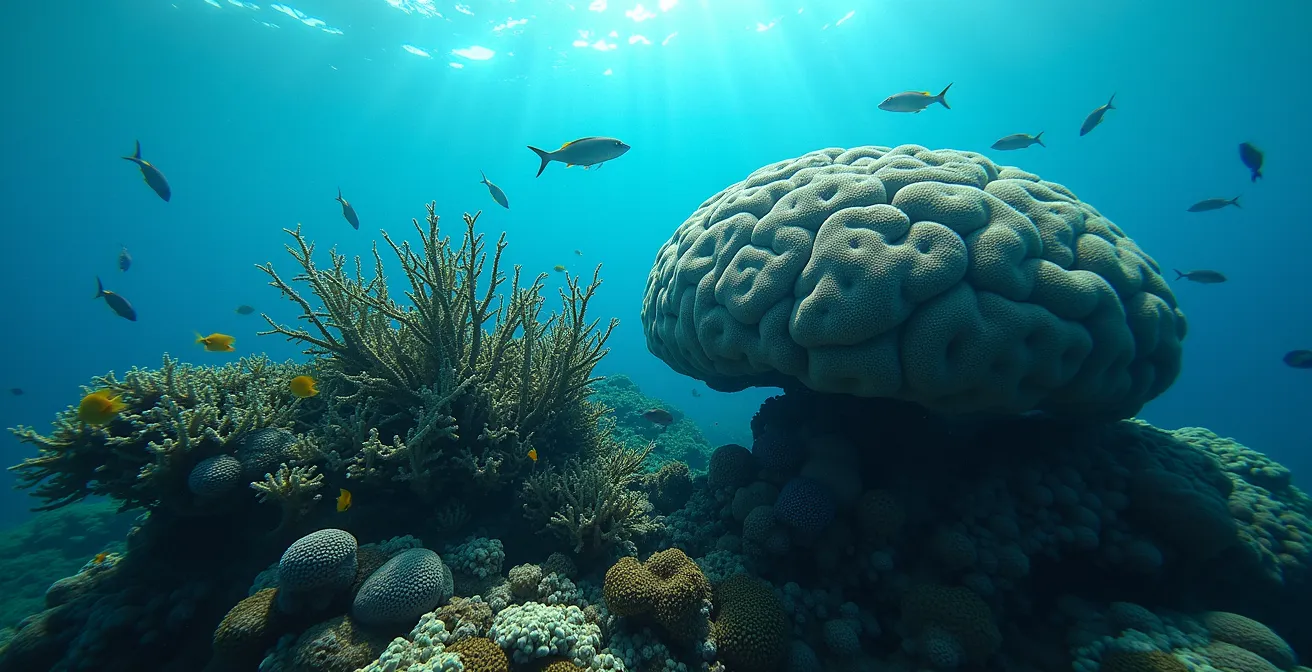

A common observation on a reef is the stark difference in life between different coral structures. A large, smooth brain coral might have a few fish hovering above it, while a nearby thicket of branching staghorn or table coral is teeming with dozens of smaller creatures. The reason is simple: structural complexity. Branching corals create a dense, three-dimensional lattice that offers an abundance of hiding places, or “refugia,” for small and juvenile fish.

This intricate architecture serves multiple ecological functions. For small damselfish, chromis, and juvenile wrasses, the gaps between coral branches are essential shelters from predators like jacks and groupers. The more complex the structure, the more nooks and crannies are available, allowing a higher number and greater diversity of animals to coexist without competing for the same space. This is a perfect example of a structural niche, where the physical environment directly enables biodiversity.

In contrast, massive corals like brain or boulder corals offer a large surface area for grazing but provide very little protection from predation. Their surfaces are too smooth and exposed. Therefore, they tend to attract larger, grazing species like parrotfish or serve as cleaning stations, but they cannot support the high-density communities of small, vulnerable fish. Understanding this relationship between habitat structure and species presence is a powerful identification tool; seeing a cloud of tiny fish tells you to look for complex coral nearby.

Day Creatures vs. Night Hunters: Which Dive Reveals More Life?

A coral reef is not a single, static ecosystem; it is two vastly different worlds governed by the sun. The question isn’t which dive reveals *more* life, but which dive reveals *different* life. This temporal shift in activity means that a reef visited at noon and again at midnight will present two almost entirely separate casts of characters. Understanding this daily migration is key to comprehensive marine observation.

During the day, the reef is dominated by diurnal (day-active) species. Colorful parrotfish, butterflyfish, and wrasses are busy feeding on algae and coral polyps, defending territories, and engaging in social behaviors. Most of these species seek refuge within the reef’s structure as dusk falls, a period known as the “shift change,” which is often the time of highest activity as day creatures retreat and night hunters emerge. A dive during this transition can be spectacular, offering a glimpse of both worlds simultaneously.

After dark, the ecosystem belongs to the nocturnal hunters and foragers. Moray eels leave their lairs to hunt, octopuses crawl across the reef in search of crustaceans, and an entirely different set of predators becomes active. To observe this world without disrupting it, divers should use red-filtered lights, as many nocturnal creatures cannot see red light, allowing for more natural observations. The following table breaks down these differences:

This comparison, detailed in a guide to observing marine life, shows that a complete picture of a reef’s biodiversity requires observing it through its full 24-hour cycle.

| Time Period | Active Species | Behavior Patterns | Observation Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day Diving | Butterflyfish, Angelfish, Parrotfish, Wrasses | Active feeding on coral and algae | Visual identification using colors and patterns |

| Dusk/Dawn Transition | Both diurnal and nocturnal species | ‘Shift change’ period with peak activity | Observe behavioral transitions |

| Night Diving | Moray eels, Octopus, Crustaceans, Hunting predators | Active hunting and foraging | Red-filtered lights to avoid disturbing wildlife |

The Camouflage Mistake: How to Spot Stonefish Before You Touch Them?

The ocean is filled with masters of disguise, and none are more infamous than the stonefish. These cryptic species have perfected the art of blending in, not just with color, but with texture and shape. Trying to spot a stonefish by looking for a “fish” is a recipe for failure. The key is to look for what *doesn’t* belong: anomalies in the pattern of the seafloor. Nature is random; perfect symmetry is not.

Instead of scanning for a fish, train your eyes to detect unnatural shapes. Look for the subtle, perfectly curved line of a mouth on a seemingly random rock, or the symmetrical bumps of eye sockets on an algae-covered surface. Another powerful technique is to watch the behavior of other, smaller fish. If you see a group of damsels or gobies actively avoiding a specific patch of sand or rock, it’s a strong indicator of a hidden predator. Even a motionless stonefish must breathe, and the rhythmic, tiny puff of sand from its gills can be a dead giveaway to a trained observer.

This skill of “negative space observation” is critical for safety and a core tenet of advanced identification. It also highlights a staggering fact: we have only just begun to catalogue the ocean’s inhabitants. In fact, UN data reveals that an estimated two-thirds of the world’s marine species remain unidentified. Spotting cryptic creatures requires advanced techniques:

- Scan for unnatural shapes: Look for perfectly curved mouths or symmetrical bumps on otherwise random rocky surfaces.

- Watch small fish behavior: Groups actively avoiding specific sand patches may indicate a hidden predator.

- Observe for gill movement: Even motionless stonefish create tiny rhythmic sand puffs when breathing.

- Use a pointer stick: Gently disturb the sand well ahead of where you might place your hand to trigger movement from a hidden creature.

How to Log Your Sightings to Help Global Marine Research?

Every dive is an opportunity to contribute to our collective understanding of the ocean. By transforming your casual observations into structured data, you can become a valuable citizen scientist. The key is to move from “I saw a fish” to a documented sighting with a hierarchy of data: species name, count, size estimate, and observed behavior (e.g., feeding, mating, territorial dispute). This level of detail provides invaluable information for researchers tracking population health, migration patterns, and the impacts of climate change.

Before your dive, coordinate with your buddy and decide on a platform you’ll use, such as iNaturalist or REEF.org. A simple dive slate is your most powerful tool. Use it to sketch unknown creatures, paying close attention to fin shapes, spine counts, and unique markings—the very details you learned to observe for identification. Importantly, remember that zero-sightings are also data. Reporting the absence of an expected species, like “no sharks observed on the reef,” is just as crucial for tracking population declines or shifts.

This systematic data collection by divers is becoming increasingly vital, complementing advanced methods. It offers a scale and frequency that traditional scientific surveys often cannot match.

Case Study: The Power of Modern Biodiversity Monitoring

The growing field of environmental DNA (eDNA) showcases the future of marine monitoring. As detailed in a 12-year study by Applied Genomics, analyzing water samples for genetic traces is revolutionizing how we track species. Their work detected 213 unique fish varieties, capturing over 150% more species than traditional trawling methods. While highly advanced, this underscores the importance of a detailed species inventory—a goal that citizen scientists directly support with every logged dive.

Your Action Plan: Contributing to Marine Citizen Science

- Pre-dive coordination: Agree with your dive buddy on a platform (like iNaturalist or REEF.org) and a potential target species to focus on.

- Document a hierarchy of data: Log the species name, count, size estimate, and any observed behaviors (feeding, cleaning, mating).

- Use a dive slate for sketching: For unknown creatures, draw their silhouette, fin shapes, and distinctive markings for later identification.

- Record zero-sightings: Actively report the absence of key or expected species, as this is critical data for population tracking.

- Upload and verify: Upload your photos and logs to your chosen platform, contributing your dive data to global biodiversity databases and making your dive count for conservation.

Artificial Reef or Natural Garden: Which Has More Fish Density?

Divers often debate whether artificial reefs, like sunken ships or purpose-built structures, are as “good” as natural coral reefs. The answer is nuanced and depends on the reef’s age and purpose. A new artificial reef acts primarily as a Fish Aggregation Device (FAD). Its complex, high-profile structure in an otherwise barren area attracts a high density of pelagic and schooling fish seeking shelter, leading to an impressive, but often not very diverse, fish count.

Over time, as a mature artificial reef (5+ years old) becomes colonized by encrusting corals, sponges, and algae, its function begins to change. It starts to support a wider variety of species and life stages, transitioning from a simple shelter to a more complex, self-sustaining ecosystem. However, it rarely achieves the full biodiversity of a healthy natural reef, which has evolved over millennia to support countless symbiotic relationships and all life stages of a vast array of species, from microscopic invertebrates to apex predators.

The most interesting phenomenon often occurs at the edge zone—the boundary where a sandy bottom meets an artificial or natural reef. This transitional habitat often boasts the highest density and diversity, as it attracts species from both ecosystems. A comparative analysis, such as the one provided by conservation organization Earthwatch, reveals these ecological dynamics.

| Reef Type | Fish Density | Species Diversity | Ecological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Artificial Reef (0-2 years) | High concentration | Low – mainly pelagic species | Fish Aggregation Device (FAD) |

| Mature Artificial Reef (5+ years) | Moderate-High | Increasing with coral colonization | Transitioning to self-sustaining |

| Natural Coral Reef | Moderate but dispersed | Very High – all life stages present | Self-sustaining breeding ecosystem |

| Edge Zone (Artificial-Natural boundary) | Highest density | Maximum diversity | Biodiversity hotspot combining both habitats |

Why Touching a Wild Animal Is Never Okay in a Real Sanctuary?

The rule “look, don’t touch” is the first commandment of responsible diving, yet the underlying biological reasons are often misunderstood. It’s not just about “bothering” the animal. Touching marine life can have direct, physiological consequences. Most fish, turtles, and marine mammals are covered in a thin, protective mucus layer, or slime coat. This layer is their primary defense against bacterial infections, parasites, and disease.

When you touch a fish, even gently, you strip away a part of this essential barrier, leaving it vulnerable to pathogens in the water. For sensitive creatures like whale sharks or manta rays, which have specific cleaning stations to maintain this coat, human contact can cause significant stress and physical harm. Furthermore, the oils and bacteria on human skin are foreign to the marine environment and can be directly harmful.

This principle of non-interference is more critical than ever. The ocean is not a petting zoo; it is a fragile sanctuary facing unprecedented threats. World Wildlife Fund estimates show a staggering 68% average decline in monitored global populations of marine mammals, fish, birds, and amphibians between 1970 and 2020. As visitors to their world, our absolute priority is to minimize our impact. The only acceptable contact is the accidental kind you actively work to prevent through perfect buoyancy control.

Key Takeaways

- Systematic Observation: Prioritize shape and behavior over color for accurate, rapid identification of fish families.

- Ecological Context is Key: Understand that habitat structure, time of day, and inter-species behavior provide more clues than visual appearance alone.

- Ethical Practice is Paramount: Perfect buoyancy and a strict no-touch policy are non-negotiable for protecting fragile marine life and their habitats.

How to Visit Fragile Ecosystems Without Leaving a Negative Footprint?

A truly expert marine observer understands that their presence is an intrusion. The goal is to make that intrusion as minimal as possible. This goes beyond simply not touching animals and extends to every aspect of your dive, starting before you even enter the water. One of the most significant and often overlooked threats is chemical pollution from personal care products. Many chemical sunscreens contain ingredients like oxybenzone and avobenzone, which are known to be highly toxic to coral reefs, causing bleaching and DNA damage.

According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), using only mineral-based sunscreens (with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide) is a critical step. Better yet, opt for UPF-rated rash guards to minimize sunscreen use altogether. Before a dive, you should be free of all personal care products—makeup, hair spray, and insect repellent can all wash off and introduce harmful chemicals into the ecosystem. This diligence is vital for protecting reefs that, while covering less than 1% of the ocean floor, house approximately 25% of all marine species.

Underwater, your technique matters. Master the frog kick instead of the flutter kick, especially near sandy or silty bottoms. The flutter kick can stir up sediment that smothers corals and other benthic organisms, disrupting feeding and respiration. Finally, choose your dive operator wisely. Support businesses that have transparent environmental policies, contribute to local conservation, and conduct thorough environmental debriefs after dives. Your wallet is a powerful vote for a healthier ocean.

Adopting this mindset of a taxonomist and ecologist doesn’t diminish the magic of diving; it enhances it. By learning to read the intricate stories of the reef, you forge a deeper connection to the ocean and become an active participant in its protection. Begin applying these principles on your very next dive to transform how you see and interact with the underwater world.